Glossary

Logout

©Copyright Arcturus 2022, All Rights Reserved.

7

Terms & Conditions

|

|

|

|

Security & Privacy

Contact

OPERATIONS - MANUFACTURING

|Generic Ideas, Suggestions & Tips

Minimise the number of manufacturing levels needed for the production of a component or a product assembly.

In the same way that every code number represents an unavoidable sequence of events, we can see that every stage in the manufacturing process (machining operations, assembly operations, adjustments, testing operations, etc.) has a negative influence on the required indirect and direct labour, on quality, lead time and cost.

It determines the layout and organisation of the factory, with additional stock-age, transportation and planning and increases the risk of rejects and ultimate quality.

Therefore, every design should be judged with respect to the required number of manufacturing levels and manufacturing process stages.

...Demand Simplicity!

Quality and reliability must always have priority.

More than ever before we can be convinced that quality and reliability always pay. The best guarantee for customer satisfaction is to deliver products that work according to the customer’s expectations and that do not need repairs.

Zero defects delivery and designs with extremely long technical lifetimes are now realistic targets, and the key lies in the product and process design.

In the total chain of a business activity, the added value increases gradually until the moment of sale. Exactly the same happens with faults. The earlier the faults are made, the larger their added costs will be. The difference with added value is that the costs of faults may keep on accumulating even after the moment of sale!

Product development is situated in the early part of the chain and therefore has a decisive responsibility for the cost structure, including the quality costs. Assembly faults may appear from time to time in a product; design faults, once they have been made, are present in all products.

Make a realistic Master Production Schedule.

This is one of the first commandments of the MRP philosophy (Manufacturing Resource Planning). It is as important as it is obvious. The extremely low delivery reliability of many factories proves that the production schedule is very often not realistic at all.

A realistic Master Production Schedule has to meet the market needs for a certain agreed and should remain stable during that period.

On the other hand, the factory must be sure that the available capacity is adequate for the planned production and that the manufacturing process and component acquisition is fully under control.

Constant monitoring of delivery performance with performance indicators are a prerequisite for improvement.

Shorten lead times by using a flow-oriented production process.

Most of our manufacturing processes can best be characterised as waiting processes, because most of the material spends between 95 and 99% of its time inside the factory waiting. Waiting time is equivalent to waste. Waste of invested capital, waste of feedback time in case of problems, and waste of labour. Measuring and analysing lead time is a powerful tool in the improvement process.

The guideline is: ‘The shorter, the better’, which automatically leads to flow-line production processes. That, in turn, leads to high quality, because a flow-line process can only be implemented successfully when it is fully under control. There is no better guarantee for quality than a flow-oriented manufacturing process. Every fault that is made results in stagnation of the flow and is therefore extremely visible to everybody in the organisation. This requires immediate action. In the case of buffer stocks these signals are delayed and the result is: slower improvement and stabilisation on a higher reject rate.

Systematically avoid operations that do not add value.

Operations that do not add value include:

- warehousing

- transportation to and from stocks

- stacking

- feeding

- repairing

- set-up time of machines and tools

The only operations that add value are those that contribute directly to the fabrication of a product or to the transfer to the ultimate customer.

In consistent flow production there is no need for intermediate stocks, no need for equipment to feed in and remove materials and no need for repair stations, because it is a controlled process. When a machine has to stop to allow new tools to be set up, the waiting time is basically waste.

However beautiful and well-designed a vibration feeder may be, it is basically a useless contraption that should be avoided by presenting the components in an orderly way, instead of throwing them into a box after their last manufacturing operation.

According to the same principle, most of our forklift trucks represent wasted money, because most of them spend their time moving material into useless warehouses and taking it out again. On the basis of the above-mentioned principles, we may come to some interesting conclusions.

One conclusion might be that we decide not to devote any of our costly and scarce engineering talent to designing ‘useless’ equipment and concentrate only on ‘productive’ equipment. In those cases where we cannot avoid ‘useless’ equipment, buy it!

Reduce the number of manufacturing levels.

Every operation that is not directly connected with final assembly represents a separate manufacturing level. Components that are mounted into sub-assemblies, sub-assemblies that are combined into larger configurations, separate testing operations, etc., all involved activities that add manufacturing levels. Every manufacturing level creates documentation throughout the production cycle, planning papers, computer work and indirect personnel. This adds up to the waste defined in the previous tip. When sub-assemblies are unavoidable, the operation should be located as near as possible to the final assembly, with visible communication and ‘pull’ type planning. This eliminates the need for a separate planning module and a separate production department, with subsequent intermediate buffer stocks.

Increase the delivery frequency per type.

Generally speaking, production departments prefer long production runs or large batches. This is not surprising, because it helps process control, avoids changeover losses, simplifies planning, and thus leads to lower manufacturing costs. It is, however, against the principles of modern logistics. In accordance with the principles of modern logistics we aim for a continuous process from raw material until the final customer, with the shortest possible lead time and a minimum of inventory. If we accept these principles, this has certain consequences for manufacturing. We have to take measures to enable us to produce the planned types much more frequently than we might prefer traditionally. In practice the seeming disadvantages may evolve into advantages. Changeover procedures must be simplified so that set-up costs are reduced, contacts with suppliers are improved, process control improves, stocks are lowered and customer service level will improve. The end result will be: better manufacturing at lower cost instead of higher cost.

Reduce the reject rate and improve process control. Do not accept an ‘acceptable’ reject level.

Process control in manufacturing is inadequate. There are many reasons for this, such as limited design quality, technology that is not properly understood, insufficient manufacturing discipline, supplier quality, etc.

In this summing up there are no ‘acts of God’, like earthquakes, floods or thunderstorms, or unexpected changes in the laws of nature. All the problems originate from human causes and can be avoided.

Therefore we should never agree on an ‘acceptable’ reject level. The only acceptable level is zero defects and the remarkable progress that has been made during recent years in improving the quality of many products proves that our previous acceptance level was actually indefensible. Measuring rejects in percentages is psychologically wrong, especially when the rejects are below 1%. Measuring in parts per million gives a new impact to the attitude towards quality. It has the same effect as looking at specimens under a microscope. Things we did not see before suddenly become visible as monsters!

Integrate suppliers in the manufacturing process as ‘co-makers’.

Suppliers (both internal and external) are involved in a high percentage of the total factory delivery value, often amounting to more than 50%. They have a decisive influence on the quality and reliability of the total goods flow and should therefore be closely involved from the design phase up to the production phase. Frequent deliveries should take place on the basis of an on-line information transfer between supplier and customer.

Co-makership means:

- Early selection of suppliers

- Involvement of the supplier during product development

- In principle, no incoming inspection

- Frequent or on-line planning and production information

- Just-in-time deliveries

- Mutual trust between supplier and customer

- No multiple sourcing and less dual sourcing

A large-scale action is needed in order to arrive at co-makership as a standard practice, understood by purchasing personnel as well as by designers, production engineers and production managers.

Introduce new planning systems only after simplifying and improving the manufacturing process.

When the manufacturing process has many levels and many stages, connected through intermediate warehousing, transportation etc., we require the system to plan and register all these phases. We then end up with a complicated, expensive system that must be run on a bigger computer than expected. Flowline production needs a minimum of internal registration and that reduces the task of the system considerably. It is therefore highly advisable to re-think the production set-up before installing a new planning system in the factory.

Improve data accuracy.

Measuring data accuracy is a critical success factor. Not only will the goods flow system operate better, but the whole chain of activities preceding it (product development, production engineering) will adopt a new style of operation that leads to better control of the creation process.

Shorten the lead time for the product from factory to point-of-sale.

The earlier new products are available on the market, the better. A week of lead time in the sales channel is just as important as a week in development. It means the cash flow begins a week earlier, the market responds a week earlier and there is one week less of capital investment.

It is advisable to monitor the lead time on a continuous basis in some of the main supply channels. In comparison with the Japanese competition, our lines of supply are shorter in many cases and we should use that as a competitive weapon.

Create a climate of continuous improvement.

Improvement drives, although often successful, tend to have a temporary character. Once the ambitious (or un-ambitious) goal has been achieved, the organisation sits back, thinking happily: ‘Thank heaven, that’s over’. The real danger is that after the pressure is off, results gradually start slipping, until the moment when –years later- another drive is initiated.

A better solution is to set long-term goals for the most important issues, based on a step-by-step improvement programme that requires constant attention. A few important performance indicators that are continually used and become well-known throughout the organisation over a number of years can create a climate of continuous improvement, provided top management shows its personal continuous interest.

Changing production behaviour and rigorous pipeline control can lead to minimal stocks.

Inventories of finished products originate from four main causes:

- Seasonal sales patterns (seasonal stock)

- Lead times and intermittent production schedules (working stocks)

- Unreliable supply channels (safety stock)

- Length of pipeline (goods in transit)

The seasonal stock can be attacked by promoting a maximum adaptation of the production schedule according to the seasonal pattern, by flexibility in working hours (i.e. 35 hours in the low season and 45 before the high season), or by hiring temporary workers for an extra shift when a peak in production is needed.

The working stocks can be reduced by organizing a constant supply of goods. This can be done by changing the production cycle from infrequent large batches to frequent small batches. When the right measures are taken for a rapid changeover from type to type, this proves to be perfectly feasible at no extra cost.

The supply channels, where direct transportation costs have a tendency to prevail over lead time and its accuracy in terms of time (combined routing with other products, or trucks waiting for a full load) should be optimised with respect to lead time and its control. When a sales organisation knows exactly what, how and when products will be arriving, it needs no safety stock.

The length of the pipeline has been discussed in the previous tip. Shortening the pipeline will certainly lead to lower inventories.

Introduce a well-discipline procedure for the Master Production Schedule.

A well-defined, disciplined and structured MPS is the indispensable interface between production and sales. It must provide information on short-term commitments and medium and long-term orientations on aggregation levels that are common for marketing and production purposes

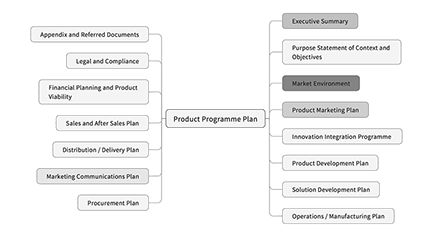

|Related Procedures

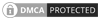

The following interrelationship maps indicate; suggested content from other models/processes which may have influence or an effect on the analysis of the title process. The left-hand column indicates information or impact from the named process and the left-hand column indicates on completion of the process/analysis it may have an influence or effect on the listed processes.

Note: A complete set (professional quality) of PMM interrelationship cards are available to purchase - please contact us for further details.

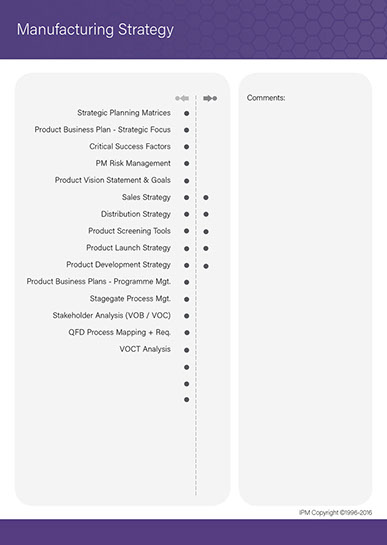

|Strategic Business Models, Workshop Tools & Professional Resources

The IPM practitioner series, is a definitive and integrated training programme for management professionals operating in the Product Management arena. So whether you’re the Managing Director, Product Director, Product Manager or a member of the Multidisciplinary Team we are confident that you will find this particular training series to be one of the best available and an invaluable asset to both you and your company.

PMM - Professional Support